Originally published on March 29, 2018.

For the past couple of years, the climate for the free exchange of ideas on social media platforms has been cooling off tremendously. Having been angered and frightened by the ability of the broad dissident Right to use various outlets to influence the election in 2016, as well as the direction in which the Overton Window has been moving, the Left has sought to shut down the ability of the Right to use these avenues for the dissemination of their ideas. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other “mainstream” social media have been fully converged and are being used by the progressive Left to suppress the distribution of Rightist ideas. We find ourselves facing an ironic situation in which platforms originally designed and intended to facilitate the free exchange of information are now being actively used to extinguish it.

Nevertheless, attempting to retain use of these outlets is a worthwhile goal for the dissident Right, especially given the less-than-impressive success of alternative efforts such as Gab and BitChute. While there are some who mock or vilify social media as “childish” or “unserious,” the fact remains that these outlets (as well as the internet in general) have a proven track record of enabling out-of-the-mainstream knowledge and ideas to find greater circulation than they would through traditional means. Social media, when used properly, provided serious users with an extraordinary opportunity to bypass the traditional information gatekeepers (print media, television, publishing houses, etc.) and to spread ideas challenging the modernist status quo. This, of course, is exactly why the Left wants to shut down these outlets.

Thus, the Right should keep using these distribution mechanisms. This will, however, require us to adapt our strategies and tactics to get around the renewed gatekeeping efforts of the Left. As even more mainstream conservative voices find themselves censored by Silicon Valley, the Right will need to increase the sophistication with which it interacts with social media. I would suggest that a primary means by which we can do this is, perhaps ironically in the view of some, to look backwards in time to the examples set centuries ago.

In his book Historical Dynamics: Why States Rise and Fall, Peter Turchin includes a chapter discussing the phenomenon of ethnokinetics. This term refers to the mechanisms and rates at which various ethnies interconvert to each other. As an example, say you had an imperial nation that conquered another ethnie, who are then incorporated as a minority ethnic group within the new empire. Depending on various specific circumstances (which can nevertheless be modeled mathematically according to general equations), over time this minority may either lose population due to assimilation or emigration, or may grow due to higher birthrates or even because some form of high status encourages individuals and small groups within the imperial ethnie to assimilate TO the minority, eventually resulting in it becoming the majority. These ethnokinetic principles don’t apply just to interactions between traditional ethnic groups, but are relevant for similar situations such as the dynamics of religious conversion or the spread of ideologies. It is these two spheres which I would like to focus on here.

We can apply these principles of ethnokinetics which Turchin outlines and adapt them to develop strategies for the diffusion of and conversion to reactionary and neoreactionary ideas. We can do this by referring to his discussion about the growth and spread of early Christianity in its first few centuries. I believe we can see some parallels to the current situation of the dissident Right. The climate in which the broad dissident Right finds itself in is not really that much different from that in which early Christianity existed. In both cases, you have an officially hostile system that methodically seeks to suppress the growth of the movement. This suppression is punctuated by periods of open persecution. These circumstances are coupled with a systematic disdain for the movement by the existing élite. At least Jack Dorsey can’t throw you to the lions or crucify you (yet).

The first observation in Turchin’s analysis is that out of the various models which have been proposed to mathematically describe the growth and conversion of minority ethnies within a larger system, the autocatalytic model best fits the historical data. This model proposes that growth in an ethnie (the term here being used quite generally) follows a logistic function. Without boring the reader with the mathematical details, this model essentially posits that growth will start out slow, but will gradually and exponentially accelerate (i.e. autocatalyse) as the probability of an individual switching from the core to the periphery (i.e., from an officially approved polytheism to Christianity) increases due to more peripheral individuals (i.e. Christians) being available to act as change agents toward remaining core individuals. Eventually, the process will slow down as fewer and fewer (formerly) core individuals remain to be converted, the system becomes saturated with the new core, and the remaining holdouts dwindle away to nothing.

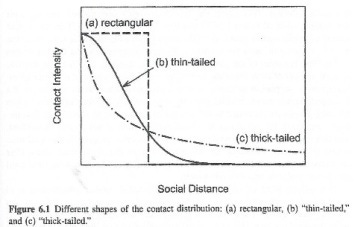

Coupled with this growth model is the concept of social space. This term denotes the sphere of social interactions inside of which any individual exists. This space has two dimensions – vertical and horizontal. Vertically, this describes the individual’s interactions with others who are above or below them in an existing social hierarchy, while the horizontal axis denotes their interactions with others who are on the same level as themselves. The intensity of interactions which any individual has with other individuals depends on a number of factors such as the relative influence they each have within a hierarchy and the social distance between them. This intensity of interactions can help to determine, among other things, the likelihood of interconversion between core and periphery, as well as the likelihood of remaining converted. It is possible to construct a graph of social distance versus contact intensity which will describe an individual’s social space (see figure below).

The important contrast in this graph is between the curves for the thin-tailed and thick-tailed distributions (the rectangular distribution can be dismissed as unrealistic for real-life social situations). The thin-tailed autocatalytic model basically posits a “front type” growth methodology in which social distance is essentially short and conversion proceeds more slowly and gradually as the area converted to the peripheral expands in along an orderly front. In contrast, the thick-tailed autocatalytic model describes what happens when individuals in the peripheral group maintain longer distance social interactions which allow them to extend their influence beyond their immediate area. It proposes faster peripheral growth as individuals in the peripheral group are able to influence more people at longer distances. This model is obviously the more realistic description of the growth of early Christianity, as can be seen from the missionary endeavours described in Scripture and evidenced among the church fathers. The uniform testimony of early Christianity is that of long-distance social interactions being maintained to first convert individuals (both horizontally and vertically) to faith in Christ, and then to disciple them and encourage them to remain converted. The figure below shows the various spatial contact models being discussed.

Turchin also notes in his discussion that the thick-tailed distribution’s growth curve most properly suggests that the methodology of peripheral growth is punctiliar rather than frontal. As distant contacts within a peripheral individual’s social network convert, or the social network is itself extended through conversion by missionary work, secondary loci for the minority ethnie are created, which then can go on to create their own tertiary loci, and on and on. Again, this is a precise description of what happened with early Christianity and its missionary work all across the Empire, as well as outside of it. For its first three centuries, Christianity was composed of autonomous local assemblies of believers, at first converted through missionary work, who maintained a long-distance social network through letters and traveling evangelists.

Extending beyond Turchin’s analysis, there are a couple of other points I would make regarding this autocatalytic growth of Christianity in its early centuries. The first is the importance of converting élites. For its first two centuries, Christianity was primarily a religion of the urban poor, with little penetration into either the countryside nor into the aristocracy of the Empire. However, around the beginning of the third century, that began to change. We begin to see members of the nobility, and especially the provincial, land-owning nobility, converting to Christianity in greater numbers. While generally not the upper crust, their conversion to Christ began the process of psychologically mainstreaming Christianity and making it more acceptable (if not believable) to many in the upper echelons of the Empire’s hierarchy. At the same time, an élite of well-respected clergymen began to arise from within as an observable élite of Christianity’s own, respected not for compromising with the pagan system around them, but for opposing it with mighty words and works. It is notable that the rate of conversion to Christianity in the Empire began to accelerate at around this time.

Secondly, we see the somewhat later example of the primarily Irish monastic foundations of the 5th-8th centuries, especially the works of Sts. Columba and Columbanus. These monasteries were generally not founded beyond the borders of the Christian world, but were founded slightly behind them, in the buffer zone where Christianisation had officially occurred, but which were still very much religiously mixed and uninstructed in charactre. These foundations demonstrated a very definite “diffusive potential” among nominal Christians and nearby pagans. Essentially, they served as places where “Christian culture” was passed on to firm up the loyalties of recent converts while also spreading the faith to pagans outside the frontier who came in to trade or seek to settle.

So, having said all of this, how does this apply to the dissident Right and our use of social media as a tool?

Well, let’s apply the lessons from above. First, we must begin to recognise that social media are not just places to sound off or to goof off, but to actually build social space. Don’t just post for the lulz, use outlets like Twitter to coordinate with others in the dissident Right. We should work to develop our own social networks with thick-tailed social distances. The unique ability of social media over the internet is that it allows an individual’s social distance to be literally worldwide, if he works to construct it. Develop our long-distance networks that can be used to target “conversion efforts” toward certain individuals or groups. The beauty of a network is that everybody doesn’t have to be in yours, but if yours is big enough it will overlap with others and allow for efficient information transfer and coordination of efforts, despite lacking a one-size-fits-all top down command structure. In many ways, this concept is similar to the “clandestine cell” system used by many revolutionary organisations. Just as Roman persecution might break up some churches in a few geographical areas, but couldn’t (and obviously didn’t) get them all, so with leftist efforts to stamp out dissident thought and action.

And a note of caution that should also be drawn from the lesson of autocatalytic growth – don’t be discouraged if growth and “conversion” seems to be slow at first. As converts to the dissident Right are made, the process will begin to accelerate exponentially.

Second, utilise the tendency toward the development of secondary loci which arises from the thick-tailed, high social distance model. This can be used to plant our people “behind enemy lines,” so to speak, by relying on the ability to contact just about anyone that the internet and social media allow. No longer are information-dealers confined to handing out pamphlets in their local neighbourhood if the broadcast and print media refuse to give them an outlet. Now, we can reach anyone, anywhere, and create “converts” in ways that the gatekeepers find increasingly hard to stop short of completely cutting off the internet. We can send out “missionaries” to practically any forum, message board, website, social media platform, and other online gathering place that we like. Thus, instead of trying to steadily grow by only reaching our next door neighbours, we can pass over difficult spots and plant our groups in the regions beyond.

Third, we should work to convert members of the petty élite to our cause. The dissident Right has already seen some success in this, and should continue to redouble our efforts. While I am not denigrating anyone’s Twitter followership counts, having a few people on our side with 100,000 followers is a much greater signal boost than having thousands of people with only 100 followers. Finding and cultivating “convertible” élites will amplify our efforts tremendously. Likewise, we should work to identify, promote, and extend the reach of worthy élites from within our own ranks, people who will hold the line on reactionary and neoreactionary ideals, while yet being able to package these for broader consumption to the “pagan” world surrounding us.

Lastly, consider the diffusive potential embodied in those monasteries which were near the frontier, but not across it. We can develop organisations that work to shore up the commitment of marginal or nominal members of the broader dissident Right movement, seeking to “disciple” them and bring them into a firmer understanding of and commitment to reactionary ideas. At the same time, we can “reach across the border” to the nearby “pagans” who are more accustomed to dissident Right ideas and who are nearer to us in their worldview and psychological framework, such as right-leaning libertarians or paleoconservatives. Rather than despising them or pushing them away, we ought to be reaching out to “evangelise” them toward reactionary viewpoints, using the fact that they’re already “halfway there” as a starting point. Monasteries in northern Italy could have a much greater influence on nearby Ostrogothic traders than they could on pagan Balts hundreds of miles to the north.

In conclusion, neoreactionaries, and the dissident Right more generally, can and should learn to use social media in a more effective manner. We know the Left wants to cut us off from being able to use it to organise and spread information. This is nothing new. The lessons of history show us how these gatekeeping efforts can be nullified.

The early Christians maintained distant relations, but they also had some pretty intense close relations. The "cells" *did* things. They met at least weekly for religious services, and they also functioned as mutual aid societies. They were rather like some of the fraternal orders of a century ago, some of which still function as pale shadows of what they once were. (The welfare state has reduced the demand.)

It is not enough to share ideas. Action begets motivation.

very interesting. I often read references to the christian expansion as an historic comparison to the rise of wokism, and how one could hope and act to stop it, but you're right that we should also consider the positive lessons of how such a world view has slowly gained ground to inspire our skills and strategies